Transportation as a System – A Planner’s View

As transportation planners, it’s our job to think deeply, on a daily basis, about transportation as a system that moves people where they need to go, as quickly, safely, and efficiently as possible. We also look at those systems as regional in scope: even when we’re looking at serving a particular destination or corridor, we have to be thinking about that location’s relationship to the rest of the metropolitan area in which it’s located. Most people who aren’t planners, however, might look at transportation very differently. They are likely most concerned with the relatively small number of relatively short trips they take on a daily basis. According to the Federal Highway Administration, more than half of all trips are ten miles or less[1]. Most people have a fairly small number of regular travel destinations—their workplace, their local supermarket, their child’s school, their house of worship, their local park, their favorite restaurant—and have little reason to think about how they might get to most other places, let alone how other people are getting around.

We planners know that the decisions that individuals make—where they go, when they go, what mode they use, and so on—have ripple effects on that entire regional transportation system, but we can’t expect everyone to think that way. As a result, there’s often a disconnect between planners and the public we’re trying to serve: we walk into a community with a great idea for a transit project, talking about improved mobility and multi-modality. Meanwhile, many people in the community see a project that doesn’t serve any of the trips they take and will probably just make traffic worse for them. There’s often a sense that we’re not listening to them: planner jargon means little to someone who’s tired of sitting in traffic for an hour to get to work every day, and just wants improvements that will get them there and back faster.

Meeting the Community Where They Are – Both Literally and Figuratively

When we do community engagement, it’s our job to meet these community members where they’re at—the people who are on board with us, the people who are skeptical, and the people who haven’t yet made up their mind. We can’t ignore the sense that many people have that they’re not being heard. Successful public engagement creates dialogue, both bridging the gap between planners and members of the public, and also putting members of the public in conversation with each other, helping them understand each other’s travel needs.

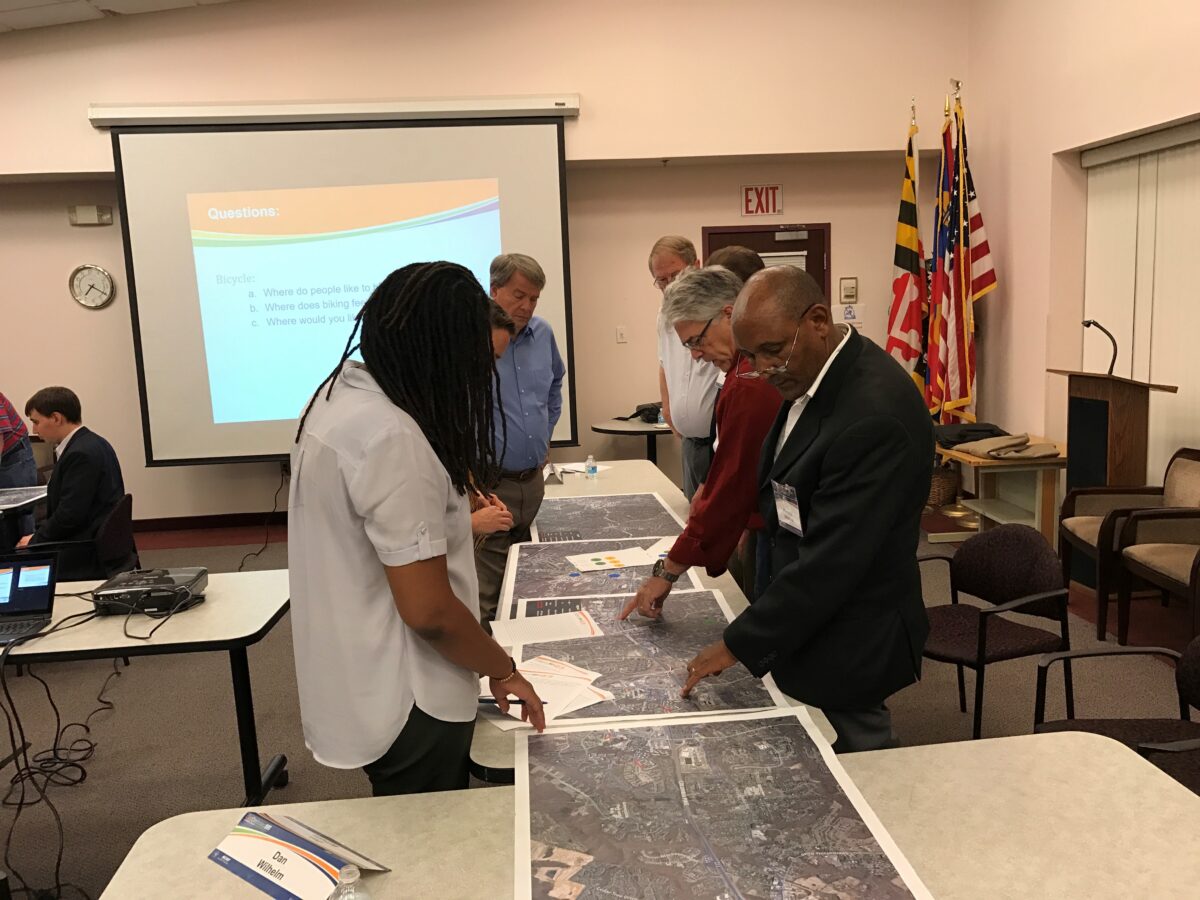

We put these principles into action at a recent series of Community Advisory Committee (CAC) meetings on a project we are working on at Foursquare ITP, along with our partners at RK&K. The project, in collaboration with the Montgomery County Department of Transportation (MCDOT), is the plan, design, and implementation of Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) service on the US 29 corridor. The CACs have been meeting regularly for two years and consist of representatives from civic groups and businesses along the project corridor. At each meeting, members of the project team help CAC members understand the opportunities and challenges of improving mobility along the corridor. But at the most recent set of meetings, held last month, we offered CAC members the opportunity to learn from each other.

Making it Informative and Fun

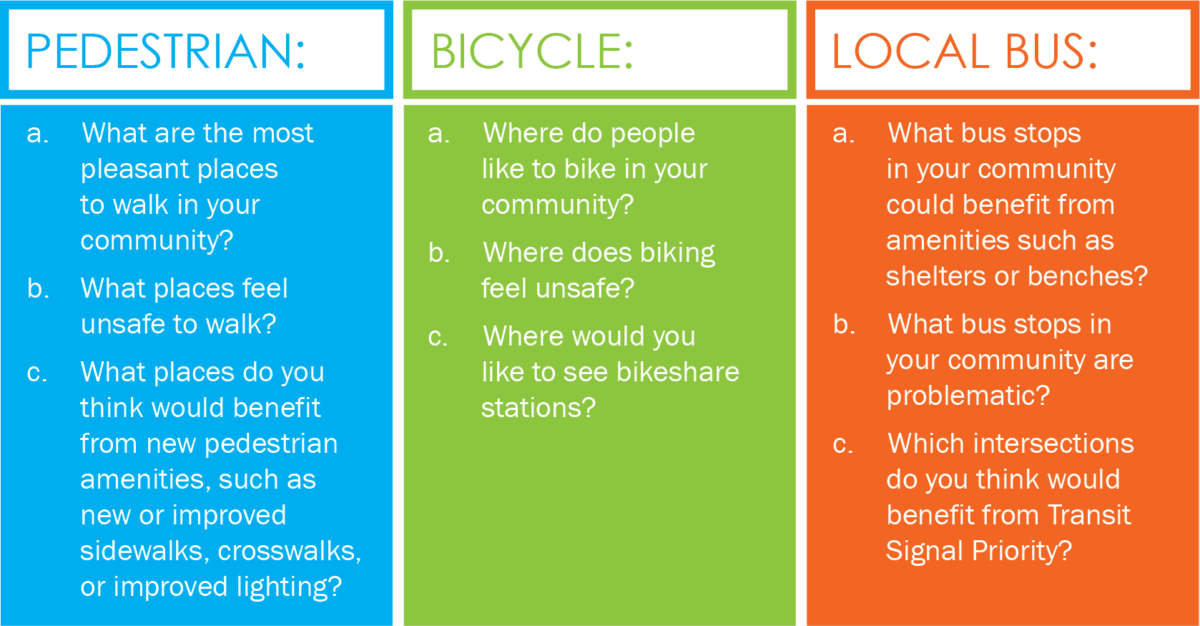

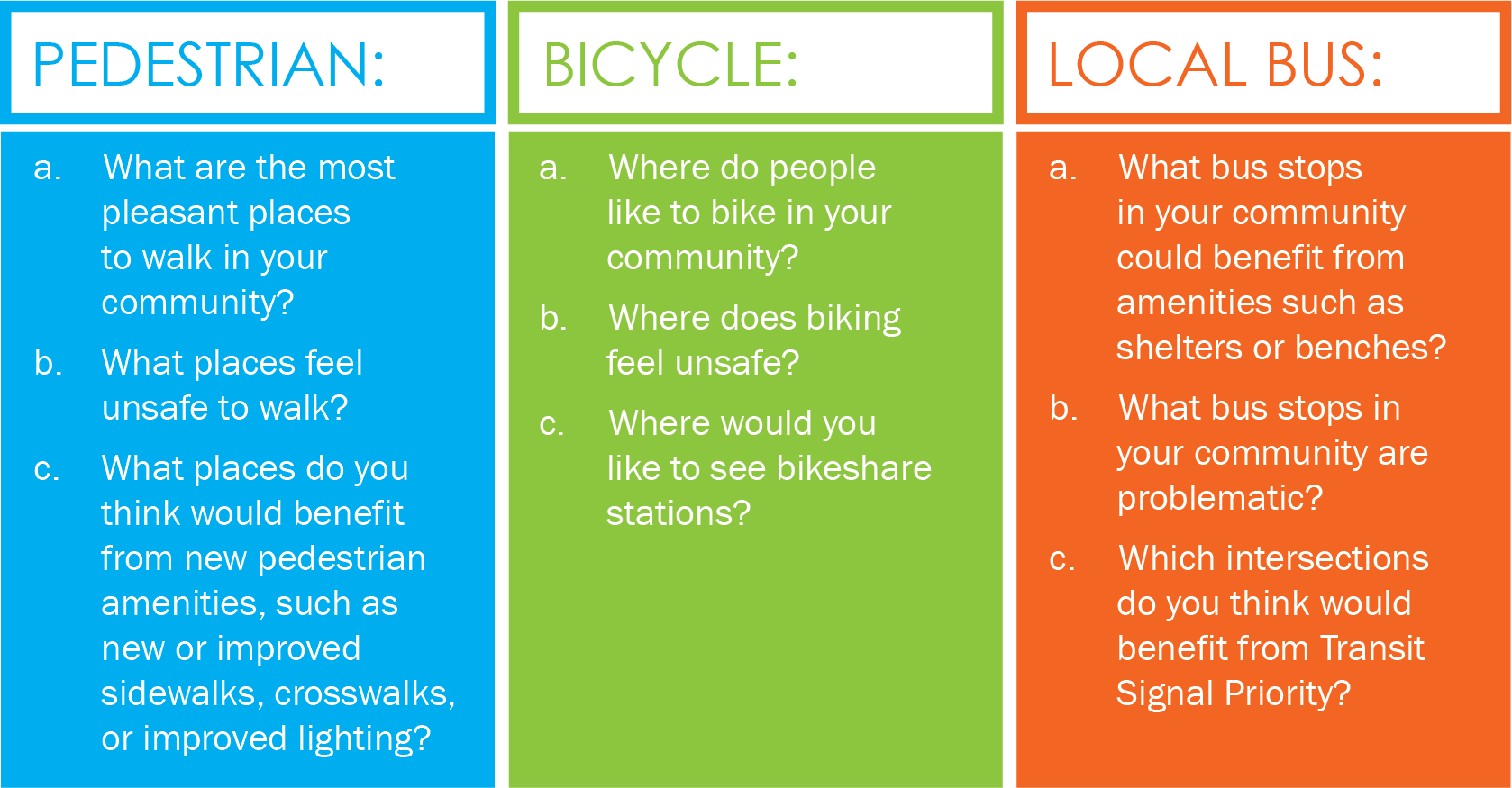

We split the CAC members into groups of 6-8 people and gave each group a set of satellite images of the corridor and its surroundings, with local bus routes, proposed BRT routing and station locations, and key points of interest—major employers, schools and civic facilities, and major shopping centers—called out on the image. Each group also received a set of note sheets and a set of color-coded stickers. On the note sheets were three sets of questions: one about walkability, one about bikeability, and one about local bus service. These questions made participants think about the constraints and opportunities for improvement for users of each mode along the corridor. Participants answered these questions by using their stickers to note locations that they thought best answered each question, and using their note sheets to record the reasoning behind each answer. Participants were only given three stickers to answer each question, forcing them to discuss each question as a group and come to a consensus about the most pressing accessibility needs along the corridor.

The questions we posed were as follows:

Groups had ten minutes to answer each of the three sets of questions. Each group had a facilitator and set time to answer the questions, and then the groups then reported back to each other on what they had come up with, which generally turned into a respectful and spirited discussion of the specific locations each group chose. These presentations proved enlightening for the CAC members. Members who traveled everywhere by car got to learn about the difficulties that people with disabilities had trying to board the bus when illegally parked cars block the bus stop. Members who would never consider biking to work heard about the experiences of those who do so regularly. Just being heard, and listening to the other CAC members discuss their experiences, provided many CAC members with a new perspective on the project.

Using the Exercise Results to Inform the Plan

The experience wasn’t just valuable for the CAC members, it was also valuable for the project team as well. We were already familiar with many of the CAC members’ concerns, but some were new to us. For instance, we learned that recent improvements the County had made to a problematic bus stop on the corridor did not alleviate concerns, as riders still felt unsafe walking to or from that bus stop. After the CAC meetings, the project team analyzed the results, creating a GIS map with every location, concern and opportunity the CAC members identified in the activity. That map was then released to the public, and can be found on the CAC’s website here.

The insights from this activity will help improve mobility and safety along the US 29 corridor, but they’re also proof of the effectiveness of a collaborative approach to public engagement. Looking at public engagement not just as top-down sharing of information, but as starting a community conversation, can help members of the public feel more included in the planning process, and help them understand the ways in which projects meet not only their own travel needs, but the mobility needs of their neighbors.

[1] Federal Highway Administration. Our Nation’s Highways, 2008. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/pubs/pl08021/fig4_5.cfm