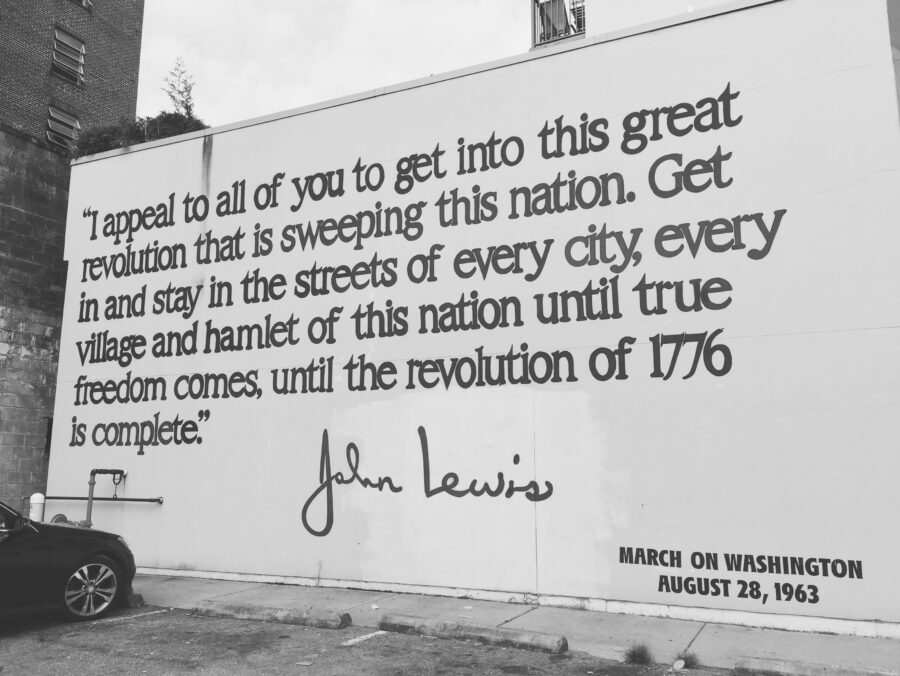

Just a short bike ride away from Foursquare ITP’s Atlanta office, you can see a quote from civil rights leader John Lewis: “Get in and stay in the streets of every city… until true freedom comes.”

At this time of year, with Martin Luther King Jr. Day just passed and Transit Equity Day just ahead, it’s as good a time as any to reflect on our role in making a better world. One of the best things about working at Foursquare ITP is that our staff understands that better transportation options and social equity are inextricably linked. As a transportation planner, I embed this tenet into my work daily.

Beyond the Back of the Bus

Most people learn about “newsy” historical events, like Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, or Martin Luther King Jr.’s most famous speech in Washington, DC. While these events were newsy for a reason, there is so much history outside of these anecdotes that illustrate how, historically, transportation has served as a tool to marginalize communities of color and the poor.

I look to Robert Moses’ influence on car-centric development in the first half of the twentieth century as an example of this. Moses prioritized limited access highways over public transportation. His highway and bridge projects, largely in the New York City area, destroyed huge swaths of affordable housing and forced out low-income residents, often on purpose. Infrastructure’s impacts last for generations; the now-divided communities that ensued from these projects remain in serious poverty to this day. Moses’ projects have a legacy of marginalizing communities of color. (Look up the history of Jones Beach on Long Island if you want to dive into that rabbit hole.)

Moses certainly wasn’t the only planner to use car-centric planning as a tool of social and economic division. The long-term result of auto-oriented planning is that communities of color and the poor are still battling for transportation accessibility all over the country, and they remain largely sidelined from an accessible transportation network. I think that if we want to improve social outcomes for those harmed—both historically and currently—by transportation planning, low-cost transportation for all is the key. Transportation, land use, and economic opportunity are inextricable from each other.

The Wheels Go Around

The way I see it, planners have no choice but to organize planning around social equity. It’s too easy for planners to abstract the problems they work on. Most of us have spent a lot of time in the intellectual cocoon of school, and then we work by thinking about the 30-years-from-now future. Nothing is urgent when it feels far away. Yet, families will struggle for generations if we don’t do our jobs correctly. They may struggle even if we are able to do our jobs right. I’m not trying to be dramatic—we know this is true.

One of the thorniest challenges we struggle with when putting equity first is the planning process itself. Planners and engineers can come to feel like they’re empowered to decide in advance what the projects should be, regardless of the community’s sense of their needs, often leaving residents blindsided. On the other hand, residents frequently act against their own interests, leaving planners feeling torn between the policies the public enacts and the public itself.

The last point is important. We’re living in a time when residents are justifiably angry and distrustful of institutions, but humans have a bad habit of contradicting ourselves in our anger.

Somerville, Massachusetts is an interesting example of this. The town I called home for nearly seven years is frequently at the forefront of enacting progressive policies, including the approval of zoning code reform to enable more density near transit. People living there are outwardly supportive of policies aimed at improving social equity, including affordable housing. However, when I was on the city planning board, community members would come to meetings and vigorously oppose projects that would increase housing affordability. The mixed signals made it difficult for the community to proceed in any direction.

When the Community Hops On

Clear communication seems to be the best way to address fulfilling the equity issues in planning. Planners, especially technical folks and consultants, need to remember that they are public servants, even if they work in the private sector. They need to work interactively and iteratively with the communities they’re working in. They need to speak and write in plain language so that the public can understand why a project may be a good or bad idea.

But I think some solutions are often too simplistic. Think about a hypothetical: a planner is following the town’s policy, adopted by the town council, to increase active transportation use. The planner looks where bicycle user deaths are highest and proposes a bike lane project. This project would occur in a primarily Black community, which may view bike lanes as a harbinger of government-sponsored displacement (remember Robert Moses?). This street of potential bike lanes is located in a Black neighborhood that historically has received less attention from city government, but the planner doesn’t ask the community first before preparing preliminary engineering. We must ask ourselves: is equity still part of the process?

Treating the community like a contributing member and soliciting their input before specific projects are on the table is essential to better planning outcomes. Critically, community involvement is itself a better planning outcome, too. What I mean by this is a strong community involvement process—even one that just gathers ideas from the community—is enough to be considered planning.

At Foursquare ITP, we integrate equity prioritization into our work. Our recent transit service planning work in North Carolina, for instance, has helped local agencies identify areas of highest need by looking at both demographics and transportation system deficiencies. We have done similar work when planning for bicyclists and pedestrians in Maryland, trying our best to help the agencies look ahead to better community involvement earlier in the planning process.

While so far, there are no one-size-fits-all solutions to ensure complete equity in every transportation project, Foursquare ITP will continue to employ all the tools at our disposal to improve public transportation for all. Visit our website to see how or learn more.